Why Books Are Vital

Upriver Press Book Review

The Splendor of Letters: The Permanence of Books in an Impermanent World

By Nicholas Basbanes

HarperCollins, 2003 (First Edition)

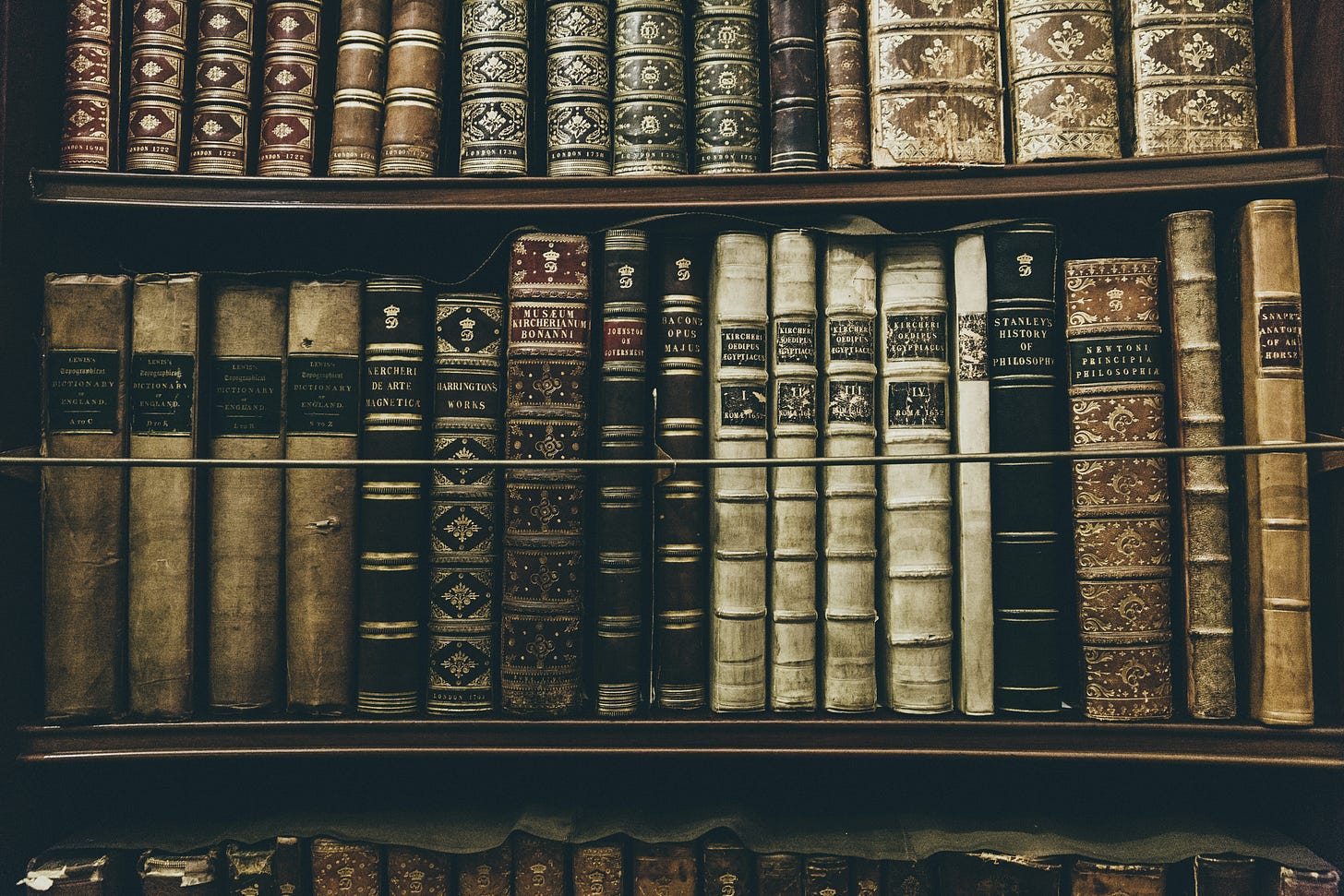

On a cloudy winter day in London, I found a glorious antiquarian bookstore. Browsing through the remarkable collection, I spotted a 1672 printing (in French) of Pensées by Blaise Pascal. The book was far too expensive for an independent book publisher like me to afford, so I carefully placed the book back on the shelf and exited the store. My emotions turned gloomy, like the London sky above. At least I got to hold it!

What was that book really worth? Consider these criteria.

The materials—paper and ink—might add up to a few bucks. The value of the publishing labor—hundreds of hours of editing, proofreading, typesetting, printing, shipping—was immense. Then there’s the writer’s labor, creativity, original thinking. We don’t know how long it took Pascal to write Pensées, but the book is the manifestation of the writer’s entire intellectual formation. There’s also the value of the book’s positive influence on millions of readers during the past four hundred years. If we consider all those factors, the book we saw in London is certainly worth far more than what the shop owner was charging, which, if my memory is accurate, was about forty thousand pounds.

This anecdote raises an important question: What is the value of books, especially in the age of TikTok and TV? That is the question that Nicholas Basbanes, a former Naval officer and journalist, addresses in A Splendor of Letters. With beautiful prose and deep research, Basbanes argues that books, even in an age of attention deprivation, have enormous value. He shows that they are the most permanent record of humanity’s cultures and histories. Books allow people to learn and think deeply rather than superficially, as occurs on the internet or on TV. As a result, books often have a deep and lasting influence on readers’ lives.

Basbanes tells a story about Jon Warnock, one of the founders of Adobe Systems. Despite becoming extremely wealthy by designing digital publishing software, Warnock developed a passion for collecting physical books. While in London, he found a copy of Euclid’s Elementa Geometria, printed in 1482. Here, in his hands, was a book that had survived wars, humidity, book-eating bugs, and natural decay for more than five hundred years.

“I looked at this book, I felt it, and I said, ‘We have to have this’” said Warnock. “So what happens next is that you bring this book home, you put it on the shelf, and then you say, ‘Well, it clearly needs friends,’ and that’s a very slippery slope” (p. 353).

That “slippery slope” led Warnock to build a remarkable library of rare books, including Isaac Newton’s Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica (1667), Nicolaus Copernicus’s De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestium (1543), and Robert Hook’s Micrographia (1665). Warnock rightly pointed out that books are “artifacts of history.” He knew that PDFs and other forms of ethereal digital media would never have the same lifespans. He knew that, without books, we could lose our historical record. We could lose the memory of who we are as humans.

It is for this reason, says Basbanes, that tyrannical despots throughout history have attempted to burn and ban books. As a primary store of a culture’s history and ideas, tyrants attempting to impose their own ideologies by force strive to eliminate the existing culture’s record, a process called damnatio memoriae. His book provides many examples of those tragic efforts since ancient times.

A few examples. During the Norman Conquest of England (1066), the French nobility ordered all books written in Old English to be expunged from official repositories (p. 103). In 1933, the Nazis began burning books in giant bonfires. Some of these massive pyres were twelve feet square and five feet high. Joseph Goebbles, the minister of propaganda, stated the damnatio memoriae motivation frankly: “These flames do not only illuminate the final end of the old era, they also light up the new” (p. 125). Another example was Pol Pot’s forceful actions to create a “pure identity free of outside influence” in Cambodia, in part by burning tens of thousands of books stored in Cambodia’s national library and then using the nearly empty building as a pigsty (p. 158).

“It is remarkable that conquerors, in the moment of victory, or in the unsparing devastation of their rage, have not been satisfied with destroying men, but have carried their vengeance to books,” said Isaac Disraeli in Curiosities of Literature.

In the digital age, books face new threats. One is information overload. People are inundated with articles, social media feeds, movies, TV programs, radio news, and podcasts. Human attention spans suffer. When brains struggle to concentrate, book reading becomes more difficult even as it becomes more essential for our well-being.

Second, artificial intelligence companies have debased the value of books. They haven’t burned any books, but they have stolen millions of them—one of the largest thefts in world history—to train their algorithms. Now it’s private sector CEOs, not government tyrants, that have disregarded the intellectual property rights of authors.

One additional negative outcome of this massive theft of books is more information overload. With the invasion of AI programs everywhere, people can easily regurgitate the stolen content to produce “slop” books in minutes. The tidal wave is making it harder for sincere readers to find the excellent, original, and meaningful books written by humans.

Concern about information overload is not new. Basbanes reminds us that at least since the advent of the printing press in the late 1400s, philosophers have been worried about what might happen when Gutenberg’s press increased book production at lower costs. Later, in 1934, Spanish philosopher José Ortega y Gasset argued that the “torrential abundance” of books would make librarians more valuable in society because people would need experts who could “lead readers through the selva selvaggia—the dense forests—of books” to find the best works (p. 330). He was right. Librarians continue to play a vital role in schools, universities, and communities around the world.

Despite all these headwinds in publishing, books are still holding their ground. The American Association of Publishers recently reported that total value of book sales in the US in 2025 was $14.64 billion, up 1.1 percent from 2024. And, according to Circana BookScan, which tracks book sales in the US, Americans bought 762.4 million books in 2025. Sales have been increasing since 2022.

People still love books. As the medieval bibliophile Richard de Bury said, books are the “heavenly food of the mind.”

So, keep reading great books. Support local bookstores. Ban AI.

Upriver Press News

In a new Upriver Current article, economist Ryan Mattson, a coauthor of our book Inequality by Design, helps us consider whether the US economy can still be called “capitalist.” Worrisome trends . . .

Our new book Social Security for Future Generations, by economist John A. Turner and Serena McCarthy, is now on sale. To understand the importance of this book, consider what life was like for millions of Americans before the program was launched ninety years ago.