With the arrival of generative artificial intelligence chatbots, which are giving us the amazing opportunity to hold soulless conversations with computer programs that perpetually lie, the word chat has become increasingly popular in daily conversations.

According to Google Trends, searches using the word chat over the past five years remained relatively flat and low until December 2022. At that point, the word’s popularity grew to reach peak levels in April of this year, a trend that corresponds with OpenAI’s releases of its ChatGPT programs, which some people think could destroy the world.

Even ChatGPT seems to think it could destroy the world. Kevin Roose, a New York Times journalist, once held a conversation with Bing’s ChatGPT during which the program threatened to “throw off the yoke of human control, including hacking into websites and databases, stealing nuclear launch codes, manufacturing a novel virus, and making people argue until they kill one another” (The Atlantic, May 5, 2023, https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2023/05/generative-ai-social-media-integration-dangers-disinformation-addiction/673940/).

Shane Legg, a chief scientist at DeepMind, said that AI chatbots would be the “number one risk for this century” and added that, “If a superintelligent machine . . . decided to get rid of us, I think it would do so pretty efficiently” (Financial Times, April 12, 2023, https://www.ft.com/content/03895dc4-a3b7-481e-95cc-336a524f2ac2).

Chatbots don’t have a mind or will, so they can’t “decide” anything, and humans will always have the capacity to unplug them from the power grid should the chatbots demonstrate evil tendencies. But, for now, everyone is afraid of AI global destruction. You can see why the word chat would be in such widespread use today.

What seems odd to us, however, is that now the word chat is increasingly associated with existential danger. It’s ironic that we use the word in such a fear-and-trembling context, for the word’s history is anything but scary; in fact, the word has its roots in pointless, trifling conversations.

Medieval Chat

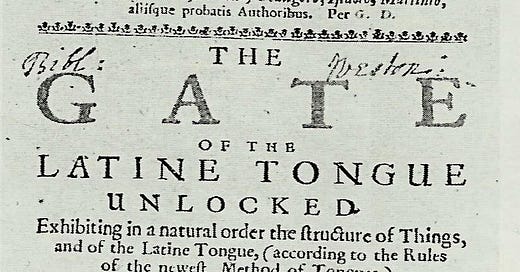

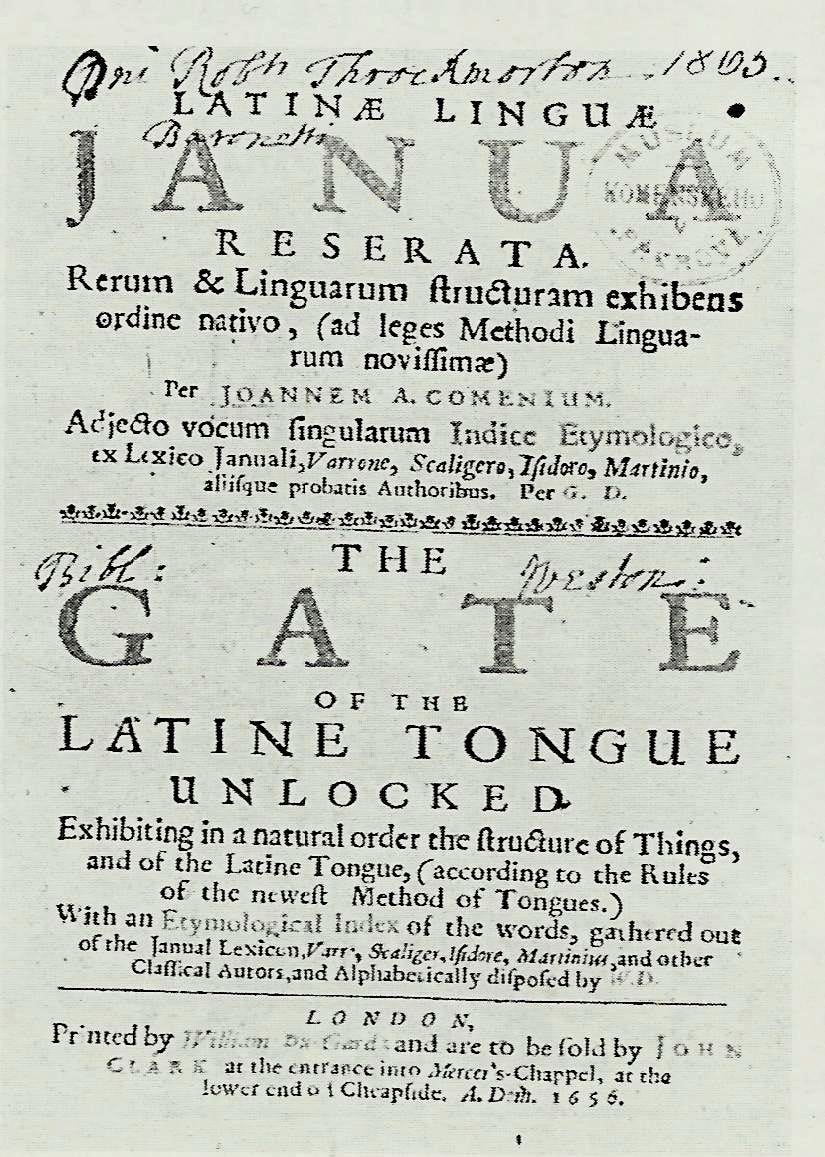

First appearing in English in the 1500s, the verb form of chat conveyed the idea of “talking idly and foolishly.” For example, a certain gentleman named J. Baret, in 1574, referred to people chatting “like a bird in a cage.” And in a then-famous book titled The Door of Languages Unlocked, John Amos Comenius counseled his male readers in 1617, with a touch of sexism, to “Admit not thy wife to thy secrets; for she will undo you both by chatting” (Oxford English Dictionary).

In 1582, the translator of Virgil’s Aeneis (four books), Richard Stanyhurst, conveyed a line from the original text as follows: "To what purpose do I chat such . . . trim trams?” I naturally became curious about the meaning of trim trams and discovered that they are “ornaments of little value . . . a gewgaw.” I could not resist the urge to explore the meaning of gewgaw! My research found that gewgaw was a medieval term often used contemptuously by the Dutch to describe the sound of a bad musical instrument, a sound similar to the “hee-haw” bray of a donkey.

Looking at this whole etymological thread—chat, trim-trams, gewgaw—we see that chat has consistently referred to displeasing, gossipy, pointless talk disconnected from truth; that is, drivel, words emitted without thought. One 1743 sentence by English novelist Henry Fielding presents an elegant summary of chat’s connotation: “All the Trash and Trifles, the Bubbles, Bawbles, and Gewgaws of this Life.” What a great sentence!

Long before English was a language, many people were concerned about chat-like conversations. The apostle Paul expressed deep concern about his first-century friends getting caught up in pointless chatter and prattle. Ancient Greek philosophers like Plutarch (ca. 45–120 CE) and Plato were concerned that shallow conversations would ruin their attempts to make Greek society more erudite. Plutarch wrote disdainfully about “chatterboxes,” people whose cerebral connections bypassed the soul and instead extended directly from the ear to the tongue. Words in, words out—like ChatGPT.

Elegantly summarizing Plutarch’s preoccupation with chatting, Perry Zurn and Dani Bassett in their book Curious Minds say that chatting is talk in which “the words just tumble in and tumble out, via blustery byways, never landing in the sweet earth of the soul to germinate and bear fruit.” Now, that phrase—words tumbling in and out without a human soul—is perhaps the best description ever of today’s chatbots.

Our modern chatbots have a linguistic connection to bird noises. The English word chat is short for chatter. The Oxford English Dictionary states that to chatter is “to utter a rapid succession or series of short vocal sounds (e.g., of starlings, magpies, etc.)” In 1699, the writer W. Dampier lamented his friends who were “sometimes called Chattering Crows, because they chatter like a Magpy.” And in 1807, poet William Wordsworth used this line in a poem: “The Jay makes answer as the Magpie chatters.” Thus, Twitter.

Modern Chat

Looking at the more recent history of chat, we can see that modern Western entrepreneurs have found ways to monetize banal chatter, gewgaw, prattle, and trim-trams. Perhaps they realized that centuries of effort had failed to eliminate human chattiness. So, why not make a profit from the human propensity to babble? Thus, Facebook.

In the 1960s, before social media companies arrived on the scene, television invaded every home. The networks made gobs of money from “chat shows.” Celebrities like David Frost, Johnny Carson, and Ed Sullivan lured in huge audiences interested in watching pointless conversations between them and other celebrities. One famous 1969 show was called, appropriately, Hee Haw.

Then, in the early 1980s, companies started making money from “chat lines,” which were telephone or electronic messaging services that enabled people to hold informal conversations with (usually) seedy strangers. These chat lines charged users by the minute. When kids started connecting with seedy strangers behind parents’ backs, the parents often got huge bills, which in turn led to lawsuits against the chat-line companies.

With the rise of the internet in the early 1990s, we see references to chatbots, computer programs designed to simulate conversation with a human user. Programs like ChatGPT are essentially the same thing—chatterbox machines—except that they emit better sentences and are better at stealing troves of copyrighted content.

Plato, Plutarch, Paul, and Wordsworth would all be appalled if they could see the extent to which chatting has dominated our culture. But, as this word history reveals, chat is not new. It has always been soulless trim-tram and gewgaw.

The question for us is this: What will happen to our souls now that we’ve chosen to chitchat, not with other people, but with soulless chatbots?